Comparing the Bootstrap and Cross-Validation

This is the second of two posts about the performance characteristics of resampling methods. The first post focused on the cross-validation techniques and this post mostly concerns the bootstrap.

Recall from the last post: we have some simulations to evaluate the precision and bias of these methods. I simulated some regression data (so that I know the real answers and compute the true estimate of RMSE). The model that I used was random forest with 1000 trees in the forest and the default value of the tuning parameter. I simulated 100 different data sets with 500 training set instances. For each data set, I also used each of the resampling methods listed above 25 times using different random number seeds. In the end, we can compute the precision and average bias of each of these resampling methods.

Question 3: How do the variance and bias change in the bootstrap?

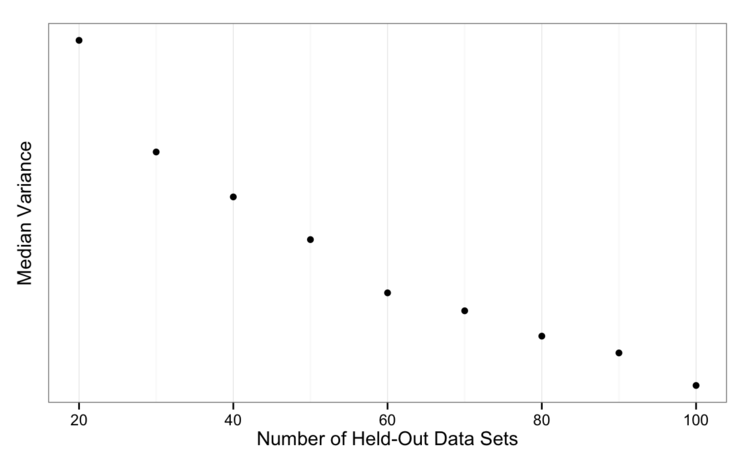

First, let’s look at how the precision changes over the amount of data held-out and the training set size. We use the variance of the resampling estimates to measure precision.

Again, there shouldn’t be any real surprise that the variance is decreasing as the number of bootstrap samples increases.

It is worth noting that compared to the original motivation for the bootstrap, which as to create confidence intervals for some unknown parameter, this application doesn’t require a large number of replicates. Originally, the bootstrap was used to estimate the tail probabilities of the bootstrap distribution of some parameters. For example, if we want to get a 95% bootstrap confidence interval, we one simple approach is to accurately measure the 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles. Since these are very extremely values, traditional bootstrapping requires a large number of bootstrap samples (at least 1,000). For our purposes, we want a fairly good estimate of the mean of the bootstrap distribution and this shouldn’t require hundreds of resamples.

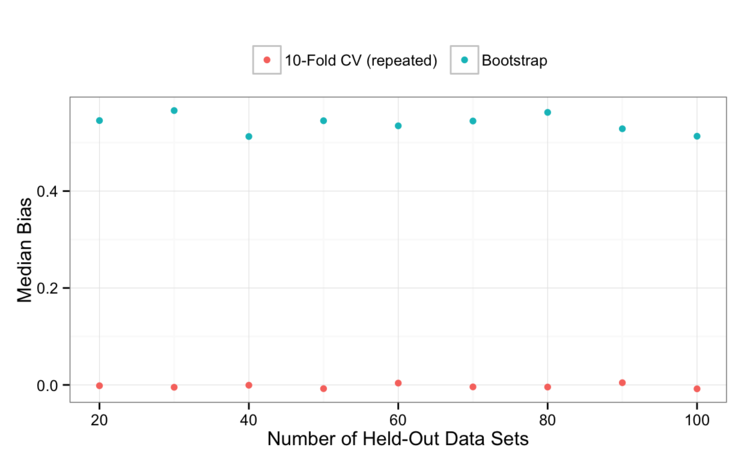

For the bias, it is fairly well-known that the naive bootstrap produces biased estimates. The bootstrap has a hold-out rate of about 63.2%. Although this is a random value in practice and the mean hold-out percentage is not affected by the number of resamples. Our simulation confirms the large bias that doesn’t move around very much (the y-axis scale here is very narrow when compared to the previous post):

Again, no surprises

Question 4: How does this compare to repeated 10-fold CV?

We can compare the sample bootstrap to repeated 10-fold CV. For each method, we have relatively constant hold-out rates and matching configurations for the number of total resamples.

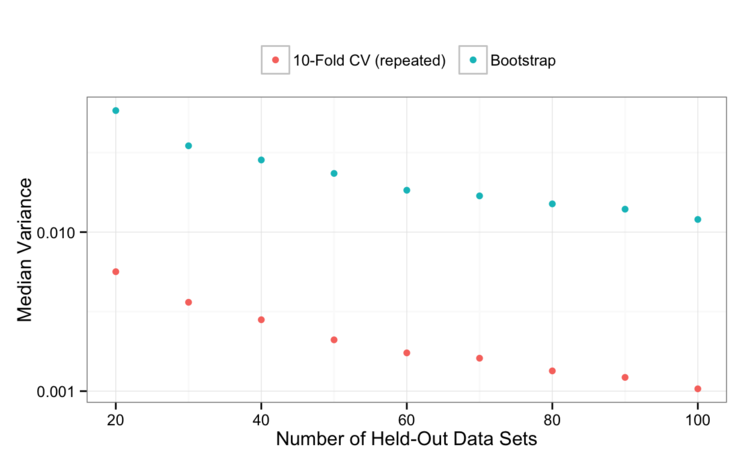

My initial thoughts would be that the naive bootstrap is probably more precise than repeated 10-fold CV but has much worse bias. Let’s look at the bias first this time. As predicted, CV is much less biased in comparison:

Now for the variance:

To me, this is very unexpected. Based on these simulations, repeated 10-fold CV is superior in both bias and variance.

Question 5: What about the OOB RMSE estimate?

Since we used random forests as our learner we have access to yet another resampled estimate of performance. Recall that random forest build a large number of trees and each tree is based on a separate bootstrap sample. As a consequence, each tree has an associated “out-of-bag” (OOB) set of instances that were not used in the tree. The RMSE can be calculated for these trees and averaged to get another bootstrap estimate. Recall from the first post that we used 1,000 trees in the forest so the effective number of resamples is 1,000.

Wait - didn’t I say above that we don’t need very many bootstrap samples? Yes, but that is a different situation. Random forests require a large number of bootstrap samples. The reason is that random forests randomly sample from the predictor set at each split. For this reason, you need a lot of resamples to get stable prediction values. Also, if you have a large number of predictors and a small to medium number of training set instances, the number of resamples should be really large to make sure that each predictor gets a chance to influence the model sufficiently.

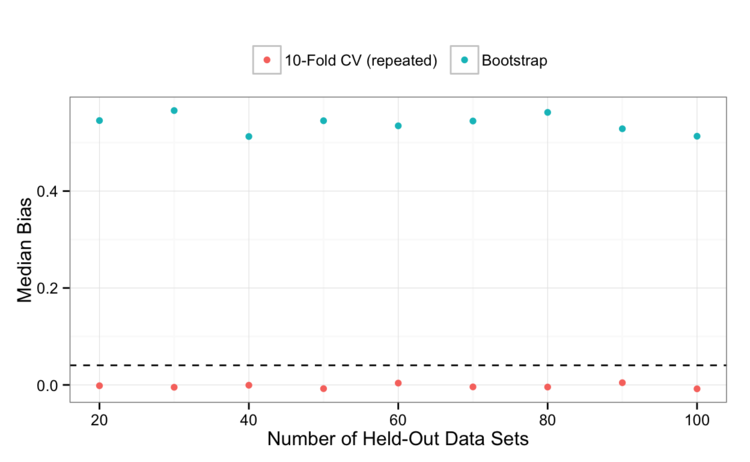

Let’s look at the last two plots and add a line for the value of the OOB estimate. For variance:

and bias:

the results look pretty good (especially the bias). The great thing about this is that you get this estimate for free and it works pretty well. This is consistent with my other experiences too. For example, Figure 8.18 shows that the CV and OOB error rates for the usual random forest model track very closely for the solubility data.

The bad news is that:

- This estimate may not work very well for other types of models. Figure 8.18 does not show nearly identical performance estimates for random forests based on conditional inference trees.

- There are a limited number of performance estimates where the OOB estimate can be computed. This is mostly due to software limitations (as opposed to theoretical concerns). For the

caretpackage, we can compute RMSE and R2 for regression and accuracy and the Kappa statistic for classification but this is mostly by taking the output that therandomForestfunction provides. If you want to get the area under the ROC curve or some other measure, you are out of luck. - If you are comparing random forest’s OOB error rate with the CV error rate from another model, it may not be a very fair comparison.

(This article was originally posted at http://appliedpredictivemodeling.com)